“Why do we draw? We draw, I suppose, because it is one of the most primitive and natural human instincts. Some thousands of years ago we would have drawn on cave walls records of the animals which the more virile members of the tribe had stalked. There is hardly a child today who, before age of reason, does not reach out for the colored crayons to record his first visual impressions, and later his first imaginings. And drawing should come as naturally as that.”

The above quote is from Robert Fawcett in his book from 1958 titled “On The Art of Drawing”.

Before I went to art school I thought that in order to learn how to draw you first had to study all the muscles and bones in the human body. After you memorized each one, and knew where they were located, only then you could draw an image with a solid foundation. Additionally, I thought you had to learn every rule of perspective if you wanted to draw buildings or cars.

What I eventually realized is that it’s not the only way to approach drawing. Yes, it’s helpful to know anatomy and understand, as much as possible, what it is you’re drawing. But it depends on the kind of art you’d like to make and where your interests lie as an artist. Also, if your focus is on strict academic rules then it’s possible that your work may lack some level of risk or life to it. The most important thing that I learned in art school is that I found a premise and a starting point with my approach to drawing. It comes from my classes at The School of Visual Arts with John Ruggeri and Jack Potter and deals primarily with the act of “seeing”. Many of the same principles are discussed in Robert Fawcett’s book that I quoted at the beginning of this article.

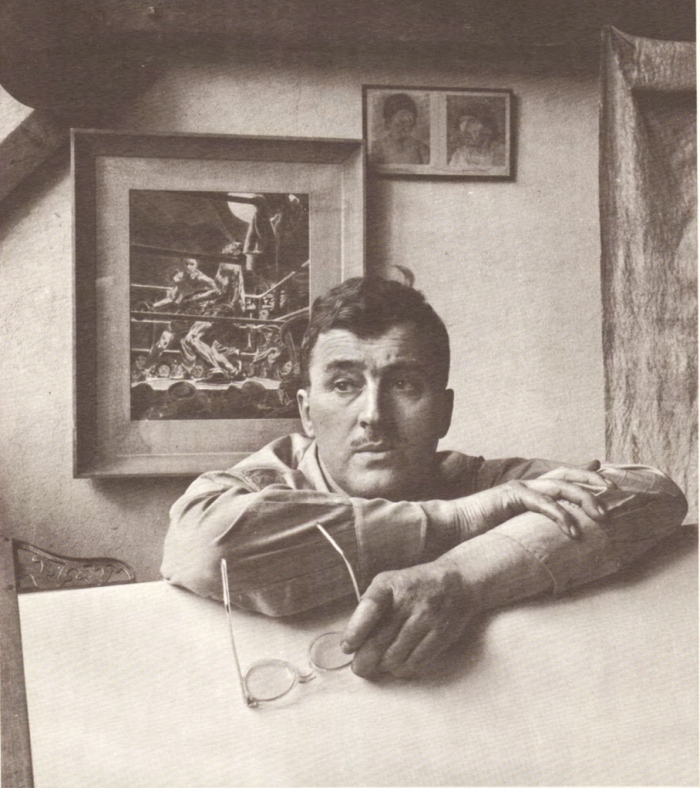

Fawcett had this to say about himself:

“I’m just a built in eye. I can see with such clarity. But the hand always falters between the eye and the paper…You can learn to see by seeing…If I have a trained eye, I will record a more comprehensive picture because I know how to translate what I see. There should be the least amount of interference between the eye, the brain and the hand. When you have exhausted conventional seeing, you can go into more interesting things.”

Robert Fawcett (1903-1967) is an artist who was born in England, grew up in Canada and studied for two years at the Slade School of Art in London. At that time the school was known for training several generations of the best draftsmen in England.

He said: “At Slade, academic and searching drawing was so insisted upon that draftsmanship became second nature. I did nothing but draw from the model eight hours a day for two years.”

Fawcett never took an anatomy class, and similar to myself, he assumed that all artists needed to learn anatomy. What he soon realized is that he was better off relying on his own power of observation than memorizing anatomical diagrams. Fawcett said: “I am not interested in exploring [the figure] by scientific means. Patella, clavicle, femur and pelvis are medical terms, not the language of drawing.”

He also had this to say about perspective: “I know very little of academic perspective – I only know whether things look right.”

In 1924 Fawcett returned to the United States where he started his career as a fine artists and after one year was rewarded with his first solo show at a Manhattan Gallery. But he soon found himself disillusioned with the gallery scene after struggling with agents and dealers for his share of the proceeds. He later said that he could not stand “the commercial side of fine art” so he decided to earn his living “by honest commercial work” instead. As far as his own work was concerned he said: “everything I do is fine art”.

By the 1930’s Fawcett was receiving steady assignments from clients such as Good Housekeeping, Holiday, Reader’s Digest, Coca-cola, American Airlines and many more. He was a busy illustrator throughout his lifetime, but was never the most popular artist during his era. Clients often hired him because they admired his level of skill and his meticulous attention to detail.

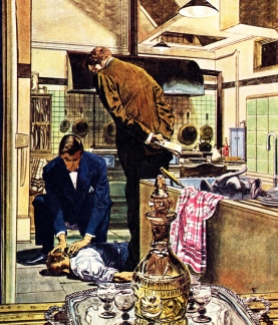

In 1948 Fawcett received an assignment from Cosmopolitan Magazine that eventually lead to what became one of his most famous illustration campaigns. It was a recently discovered and unpublished Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who was no longer alive at this time). However, it turned out to be fake and the Doyle estate took Cosmopolitan to court.

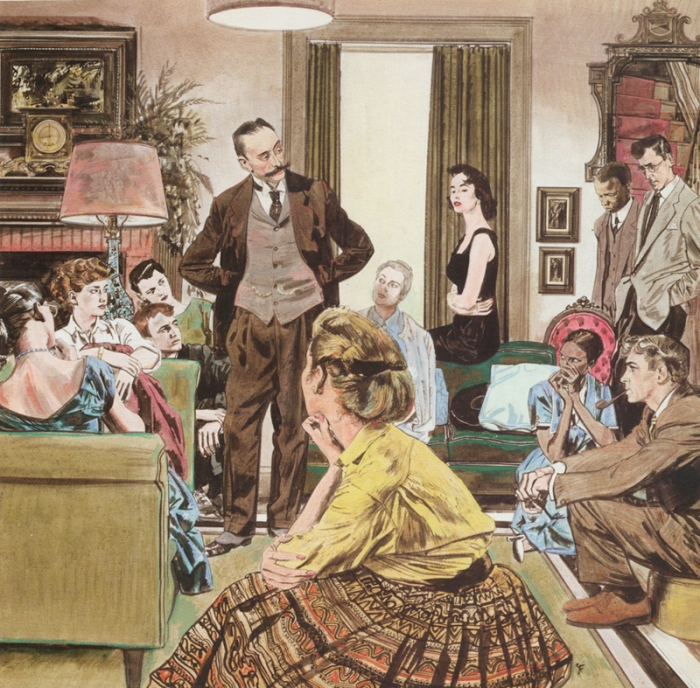

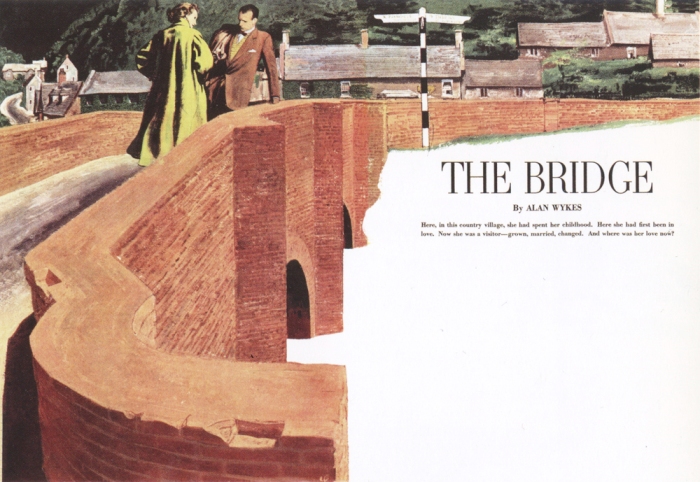

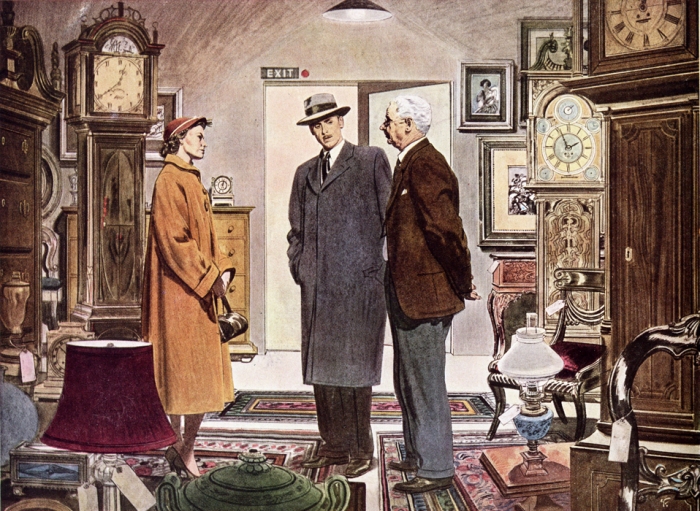

After a long legal battle, the Doyle estate responded to the public demand by working with Collier’s (the magazine that originally published Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s work) with a new series of Holmes stories that started in 1953. Fawcett went on to create illustrations for 11 new stories written by the son of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and mystery writer John Dickson Carr.

Look at how detailed and well crafted those compositions are. Not bad for someone who never took an anatomy class and doesn’t understand much about academic perspective!

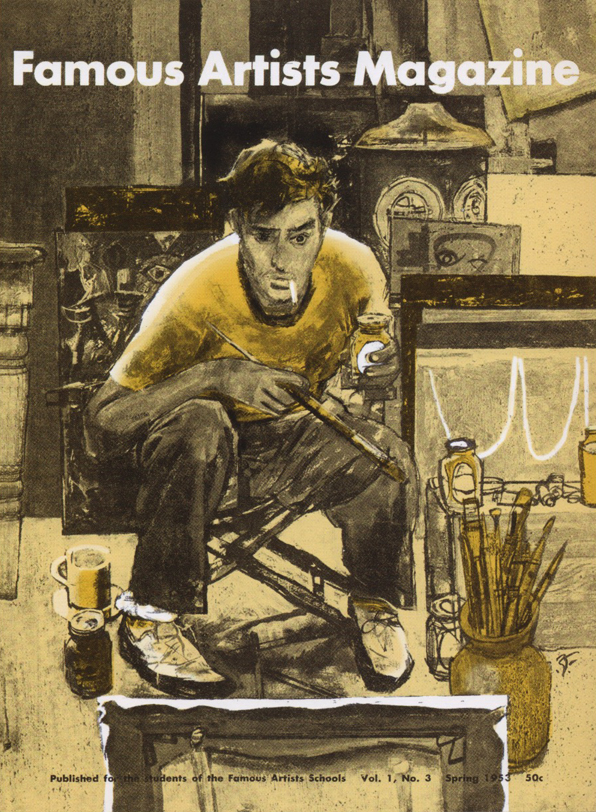

As his career progressed his reputation as a skilled draftsman became known not only with his clients, but also with his fellow illustration professionals. By the late 1940’s he was regularly sought out by publications such as American Artist for his opinions on being a commercial illustrator. He was then called “The Illustrator’s Illustrator”.

In “On The Art of Drawing” Fawcett had this to say about accuracy in a drawing:

“Although I do believe one should try to draw accurately, I do not believe that fine draftsmanship is synonymous with exact accuracy. It is usually based on “the thing observed,” which, distilled by the personality recording it, may become quite distorted from the original. The test, if we can presume to put a yard rule to something so ephemeral as drawing, is whether it gives the impression of reality over and above superficial resemblance, and whether the drawing provides an emotional stimulus quite apart from its own subject matter.”

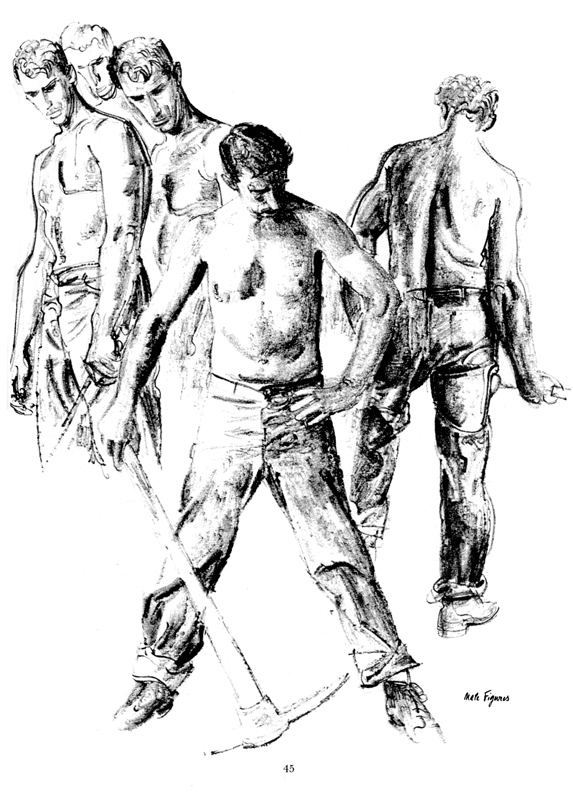

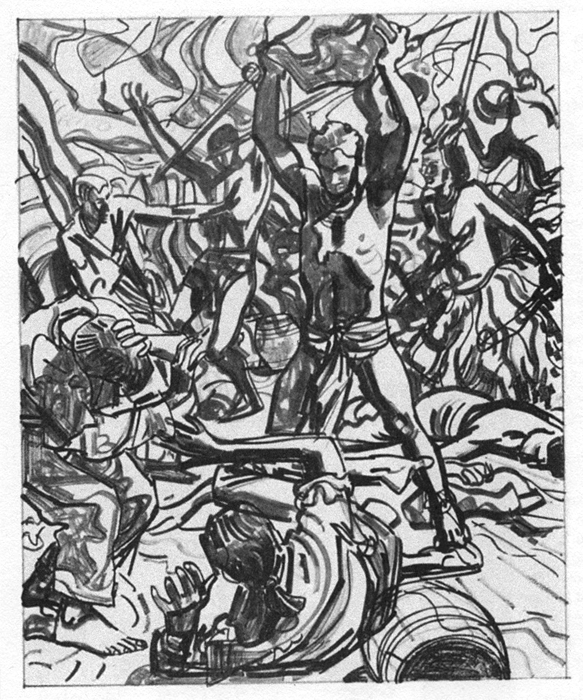

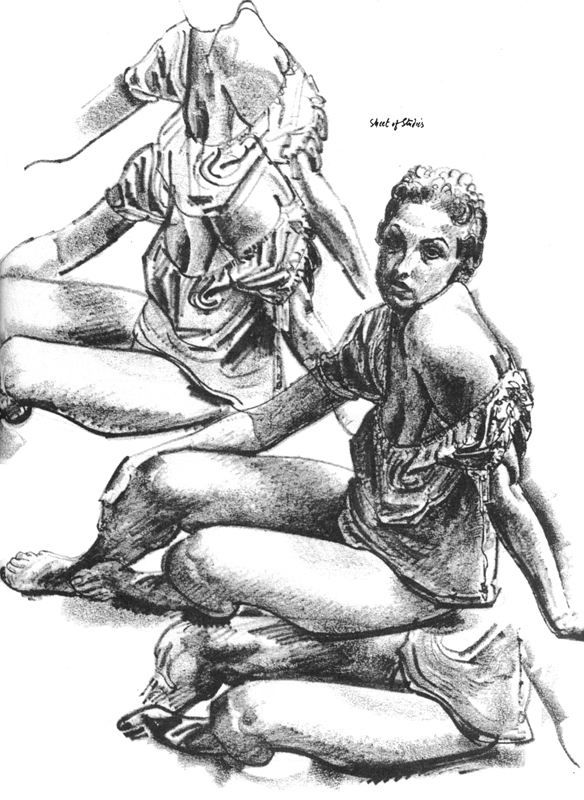

Let’s take a look at a sketch that he did for a client:

And then the final drawing:

Fawcett was always looking to improve and never rest on his laurels. He said this about life drawing classes:

“That we go to life class to “memorize” what we see is also hardly credible. There are some who will later develop the ability to reproduce, without benefit of the model, a quite extraordinary approximation of the human figure. But in comparison with what the eye really sees when confronted with the actual subject, their result will not be impressive. It is hardly an accomplishment which contributes to fine draftsmanship, but is largely a trick which can soon become a formula. It is useless to deny that the ability to do this will develop, and sometimes to a high degree, for the memory cannot be stifled. The point we make is that we should not set out to gain this aptitude; it is not the prime consideration in the development of the draftsman. For as long as possible we should try to prevent ourselves from approaching drawing with anything but an open mind and a willingness to surprise by what we see. If we are going to try to memorize the human figure, then we should consider memorizing the look of everything else in the world, also.”

I think every artist that has spent time developing their work has a specific look too it, but as Fawcett points out above some stop growing because they no longer see the world around them. I’ve seen it before, an artist who is very good at drawing out of their head or from a photo and then, when confronted with a life model, the final result is lacking. It’s generally an image that might appear to be solid at a first glance, but with a closer look you can see that the life model was barely observed at all. Drawings like that tend to look the same whether the artist drew with or without the model.

However, some artists don’t want to draw from life and can still produce an excellent body of work. But in my opinion if an artist isn’t looking at the world around them (not necessarily drawing) then the work often ends up becoming a bit stale and repetitive.

When I first encountered Robert Fawcett’s artwork I thought it was too detailed and classical for my tastes. On it’s surface it might appear that way, but when I looked deeper I realized how well crafted his images are and noticed all the wonderful textures in them. If you zoom in on his illustrations, you’ll notice that he even used abstract marks to convey a feeling or give life to an image.

For anyone who is not familiar with his work I think it’s worth taking a deeper look into it. His book “On The Art of Drawing” is also worth seeking out because it’s his philosophy on drawing.

Below you’ll find a gallery of various illustrations by Fawcett. Enjoy.

Cool man… Cool…

This is magnificent work. I know very little of Fawcett’s art, thanks for this article.

Love Robert Fawcett’s work. A feast for the eyes with all those details. I’ve tried to look this up, but can’t find anything. How are the colors images produced? Does he paint on top of a drawing? The color looks almost like it’s on a separate “layer” from the drawing. I’ve never seen an original of Fawcett’s work and am curious what it looks like/ how he works.

How are we just finding this blog? Thanks so much for this gorgeous post. Just spent waay too long looking through Fawcett’s work. A total master – thank you!

How are we just finding this blog? Thanks so much for this gorgeous post. Just spent waay too long looking through Fawcett’s work. A total master – thank you!