In this interview, we explore the concept of ‘luxury branding’, how luxury brands differ from high street brands, and current trends in the luxury industry.

Philippe also provides examples and guidance for anyone considering building a true luxury brand.

Table of Contents

1. How would you define the term ‘luxury’?

This is a tricky question to answer. The word can represent so many good and bad things to each of us, especially at a time when so many have had their livelihoods destroyed by COVID-19 and digital disruption.

We are all rethinking the term ‘luxury’ just as we had to do at different moments in history. Many who produce ‘luxury’ goods, such as Hermès, have always avoided using the term ‘luxury’, choosing to speak of quality instead, and those that emphasize luxury are typically selling ‘bling’.

Until the twentieth century, Persian blue rock salt and other types of sea salt along with black pepper from India used to be considered luxury goods. Today they are commodities.

While fur coats and crocodile bags are still considered luxuries to some, they are simply termed cruel or vulgar by others. Ivory, rhino horn, and other animal-derived materials, as well as items produced by child labor and other forms of slavery, can no longer be considered luxuries. Yet exotic and ethical bean-to-bar chocolate from ‘haute chocolatiers’ (such as Pierre Marcolini) are undisputedly appreciated as little luxuries in France and Japan.

The idea of ‘luxury’ implies something that we desire but don’t actually need. In reality, it is a true luxury to have time, love, good health, and a healthy environment. You cannot buy these, but then again, they may be considered basic needs, not wants.

Our personal criteria for ‘luxury’ include a certain rarity, impeccable craftsmanship, high creativity, and refinement. It is usually something or an experience that is outstandingly and surprisingly beautiful, memorable, and delightful. Beneath it all, we have added the notions of ethics, sustainability, sincerity, and meaningfulness to our criteria.

A healthy planet must come first, and the luxury industry will soon be showing the way. Most are now in the process of urgently re-inventing themselves.

2. What is a luxury brand?

The term ‘luxury brand’ means different things to everyone. In fact, the words ‘luxury’ and ‘brand’ are as opposite as east and west. For insiders, the big divide is primarily based on the production process. Industrially produced goods will always be considered a lesser luxury than unique pieces made by master artists or craftsmen.

‘Branding’ has been with us since the beginning of time, implying the scarification of a human or an animal by hot iron or by tattoo, carving, or stamping. The term ‘brand‘ and the ideas of ‘brand management’ are very much linked to the industrial revolution and the automated production of items such as china, soaps, or soft drinks that were all previously hand-made luxuries.

In reality, industrially produced fine China such as Wedgwood could represent the emergence of the hybrid term, ‘luxury brand’. Yet, we would speak of luxury goods, luxury labels, luxury houses, or luxury retailers.

At the end of the 1980s, many luxury labels had followed the strategies of the Parisian fashion designers – Pierre Cardin and Yves St. Laurent – to license their names across different industries across the world, and had in essence evolved into the hybrid term ‘luxury brand’. They were now also competing in the mass market. A luxury label with a luxury image was now applied to industrially produced objects, such as perfumes and sunglasses, to scale and generate massive revenue. This activity, in turn, funded the luxury image-building ventures.

This massification paved the way for industrialized high street brands, such as Ralph Lauren, to emulate the haute luxury houses in all superficial features, including the ‘designer name’ – but without the creative talent, artisanal quality, know-how, and depth of the master-in-the-house ‘luxury’ model.

3. Could you please expand on the difference between ‘industrialized’ and ‘haute’ luxury brands?

The French term ‘haute’ signifies ‘higher’ or ‘higher than’. The ‘haute’ implies that the creative person or the craftsman, studio, or house (French: maison) is the visionary, the creator, the god, the expert, the one setting the standards, not the client. The ‘haute’ person is a ‘master’ at something, and that something is expressed in the masterpieces they create. ‘Haute’ also implies that the master and his or her assistants produce ‘by hand’ – which does not mean that mechanical assistance is not permitted or is out of bounds – but it does imply no automation or production line.

The creation of the masterpieces takes time. Once the luxury goods are produced robotically in an industrialized manner, the ‘haute’ status falls away, and the term ‘brand’ comes into play.

The closest a proper luxury house could go towards industrialization would be to employ a maximum amount of master craftsmen to produce top-quality creations from the start to the end of the creation process.

For example, the Hermès Kelly and Birkin bags are never made on a production line, with one person starting the process and others completing it.

FP Journe, the luxury watchmaker in Geneva, calls his company a ‘manufacture’ to imply that all his one hundred or so master watchmakers make each watch themselves from the beginning to the end. As such, Journe can rarely produce more than 900 to 1000 pieces a year versus Rolex, producing five million watches per year.

4. How to build a strong and successful luxury brand?

Many of today’s leading luxury brands, such as Chanel, Dior, Vuitton, and Cartier, were resurrections of relatively dormant brands in the 1980s.

Karl Lagerfeld and the Wertheimers – owners of Chanel – showed the way with the revival of the house in haute couture. Bernard Arnault followed suit by reviving the ‘sleeping beauty’ house of Christian Dior. Their incredible renaissances are now as much part of branding history as is the rebirth of Apple.

Both Chanel and Dior applied the classical luxury pyramid model by starting with an expertise at the high-end, reducing distribution of fragrances, or buying back licenses to gain complete control and expand by opening brand-owned retail stores across borders.

As a result, investment funds have rushed around looking to buy dormant brands. Prominent examples include Lanvin, Balmain, or Vionnet.

The traditional way of building a strong luxury house still applies today.

A contemporary example would be New York-based, Taiwanese-born high jeweler Anna Hu.

This exceptionally talented former cellist was smart enough to acquire knowledge from the Gemological Institute of America and FIT in New York. She later received her Masters in Art History from Parsons School of Design followed by a Masters in Arts Administration from Columbia University. During this time, she interned at Christie’s and worked in the stone purchasing department at Van Cleef & Arpels and in the jewelry merchandising department at Harry Winston. She was also fortunate enough to have been born into jewelry and grew up playing with precious stones just as we grew up playing with Lego.

She has since made history as the first Asian jeweler to be featured in a solo exhibition at the Louvre’s Musée des Arts Decoratifs and broke the world auction records for the highest price paid for a contemporary jewelry artist. Anna Hu can name many celebrities today her clients, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Madonna, Emily Blunt, Natalie Portman, Naomi Watts, Uma Thurman, Scarlett Johansson, Drew Barrymore, Hilary Swank, or Oprah Winfrey. When the time is right, there will be nothing to stop her from becoming the world’s next Cartier. She is taking her time to build her image – and that’s exactly what makes her such a deadly competitor.

One of the most remarkable rags-to-riches stories in hard luxury is the story of Laurence Graff, who was titled today’s ‘king of diamonds’ by the New York Times.

Unlike Anna Hu, he grew up in the rough East-End of London and started his career as a 15-year-old apprentice in London’s Hatton Cross jewelry district. Graff was smart enough to recognize the beauty of Australia’s conflict-free pink diamonds, which were completely unexploited. Diamond conglomerate de Beers focussed at that time on promoting the clear D-color diamond to fit with the ritual of engagement that they had formed to create a desire, want, and ‘need’ for diamonds.

Graff made a stunning pink broach fit for the Queen of England. He, however, presented it to the Sultan of Brunei in a London hotel room and sold it in two minutes. Graff never looked back.

Once you have made a great masterpiece and sold it to a prestigious person, the rest comes easily. It is far more complicated to begin as a low-end mass brand such as Pandora or H&M and then try to move upwards. It’s a question of perceptual gravity.

5. How do luxury brands create desire among consumers?

Regarding desire, how can one explain the concept of love at first sight?

My friends Ind and Iglesias (who authored an excellent book called “Brand Desire“) say that “desire is deeper than a want or a need and more immediate than love. Desire is a passionate emotion. We don’t decide to react in a certain way, we just do”.

We explain it as “I want it because I want it”.

Desire is driven by our need for change. We like to desire what we can’t have – the desire to see someone, be with someone, or experience something. We love the feeling of desire. Desire motivates our actions.

Sadly we may lose desire once the person or object becomes familiar – the fulfillment of desire often leaves us with a feeling of emptiness.

The beauty of luxury is that most of us will be unable to experience or possess the luxury that we desire, so it keeps our desire on fire. There should always be something a bit out of reach or difficult to obtain – whether it’s a hand-crafted yacht, car, dress, timepiece, handbag, eyewear, or perfume. It is lovely to wait for something to be created for us.

6. What kind of impact did COVID-19 have on luxury brands/the luxury industry?

I don’t imagine that the luxury industry has been hit this hard since the black death of the 14th century – especially in the fields of travel, hospitality, fine dining, retail, culture, and entertainment.

It has certainly forced the world to reflect, to prioritize the health of our planet and its inhabitants while forcing most to succumb to online sales in one way or another. As most encounters now occur online in portrait mode, jewelry, cosmetics, and even cosmetic surgery seem to have been boosted relative to fashion other than homewear.

7. Besides COVID-19, do you notice any trends in consumer behavior regarding the perception and consumption of luxury brands?

- We are undoubtedly witnessing a total shift towards ethical / ‘sustainable’ luxury, including a strong pro-vegan or cruelty-free mentality leading to an avoidance of animal-derived materials altogether. Sadly, many millennials fail to realize that many environmentally harmful materials such as plastics are being sold as vegan-friendly!

- We are also noticing a certain luxury fatigue and a return to less consumer-oriented ways of living. However, in line with this is also a greater appreciation of high-quality goods that last, versus fast-fashion and other relatively waste-generating activities.

- Lab-grown diamonds and lab-grown “nature identical” animal skins are already in greater demand. Little thought is given to the enormous amount of communities whose livelihoods rely on the mining industry.

- In a similar vein, we are witnessing a trend towards buying food, fashion, and whatever else locally – also without a thought given to the countries and communities that completely depend on exports to survive and could be forced to emigrate.

- The sharp increase in unemployment worldwide – due to both the Amazon effect and other digital disruptions and the pandemic – is giving rise to a shrinking middle class in the west, greater social unrest, strong anti-immigration sentiment, and ultimately a certain jealousy of wealth and anger against luxury brands. People tend to forget that these are the very companies that create fulfilling jobs, pay workers well, do not replace craftsmen with robots, and often support local communities.

- Finally, it has made the need for digital strategies a priority.

8. How are luxury brands responding to these trends?

- Luxury brands rush to connect to online platforms such as Farfetch, Tmall, WeChat, and the like. Challenger brands are becoming big players via Instagram alone.

- We are certainly witnessing a total shift towards ethical / ‘sustainable’ luxury. This includes a strong pro-vegan mentality meaning that all houses that have been built on ‘noble materials’ – usually implying animal pelts and the like – including Hermès, are rethinking their traditional positions and philosophies.

- The circular economy has fast become a priority and a reality. ‘Waste’ is finally being considered as a resource. Instead of burning unsold stock, luxury houses are now either disposing of them online under the guise of ‘used goods’ rather than marked-down goods, recycling the goods, or placing this stock on the rental market that has gained respectability.

- What is certain is that the growth of non-industrialized luxury goods and services leads to greater employment opportunities relative to robotic automated goods and services. As such, it is wonderful to witness new luxury houses emerging from almost every country in the world.

Thanks so much for your participation, Philippe!

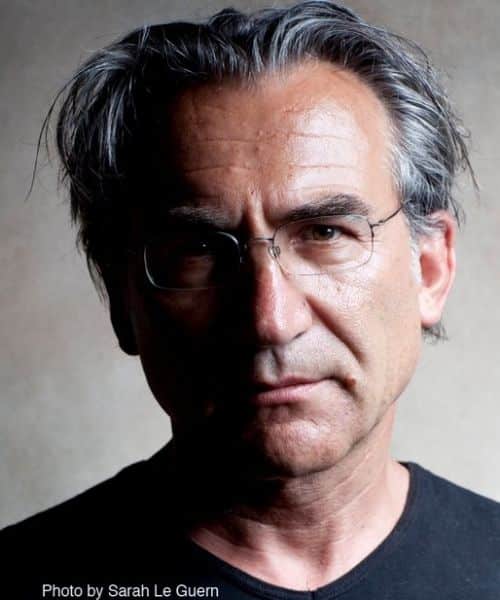

About our Interview Partner

Philippe Mihailovich is the founder and CEO of the discreet luxury branding consultancy HAUTeLUXE in London and Paris. The agency mostly consults directly to the CEOs of Luxury Houses or their Artistic Directors. He is a founding theorist of Brand ArchitectureBrand architecture defines the role of each brand and acts as a guideline for the interrelationship between the brands in your organization. and has worked as a brand management practitioner in Johannesburg, London, New York, and Paris. His latest book, Haute Luxury Branding, provides unique strategic insights for luxury branding and reveals how true haute luxury artists and maisons differ from brands.

* Portrait photos by Rupert Skinner (top) and Sarah Le Guern (bottom)