The United States has the dubious distinction of offering no copyright protection for the design of typefaces — at least not in their visual form.1 With the advent of digital fonts, type manufacturers found a way to protect their intellectual property by submitting typefaces for copyright in a format the government did accept: as font software, the computer instructions for placing the points and drawing the curves.

It was under this definition that an oft-cited 1998 infringement case was decided in favor of font maker Adobe over SSI, a company that cloned digital fonts. This workaround is now apparently in question. A change was revealed earlier this year that would essentially delegitimize fonts as software, requiring “each line of the software code” to be “written by the author”. The development caused some type designers to wonder if US lawmakers might ever reconsider the question of whether a typeface design itself should be legally protected.

Perhaps the last time this happened was in 1975, when a judiciary subcommittee from the House of Representatives held hearings on the subject. I recently discovered that the statements and transcripts from the proceedings are all available at the Internet Archive, thanks to a scan contributed by the Boston Public Library. For type lovers, it’s a wonderful document, packed with fascinating evidence, arguments, and dialogue.

Presenting witnesses included various members of the type industry, including Mike Parker of Mergenthaler Linotype, George Abrams of Alphabets, Inc., and Aaron Burns of International Typeface Corporation (ITC).

While most companies in the industry made their money from typesetting equipment — such as Mergenthaler with its Linotype machine, or manufacturers of phototype machines — ITC was the first corporation to depend on revenue from font licensing, so they naturally led the cause for copyright protection of type design. Earlier in 1975, backed by the AIGA, they advocated for their position in U&lc (Vol. 2, No. 1), a publication widely read by graphic designers. Then, in July of that year, they took their case to the government.

In a letter to the the subcommittee, the US Register of Copyrights at the time confirmed that it was a discussion worth having.

“I call to your attention the recent, very strong movement among individuals and groups of artists (painters, sculptors, and creators of fine, graphic and applied art) for more effective protection. Proposals have been advanced for amendments to the copyright law for this purpose, including registry schemes and opportunities for artists to share in the profits for later sales of their works. I believe these proposals deserve to be heard by your subcommittee.” — Barbara Ringer

As one might expect, the congressmen had difficulty wrapping their heads around the concept of original typeface design.

“I will tell you what my problem is … It is tough for me to imagine 10,000 different ways to make an A.” — Rep. Charles E. Wiggins

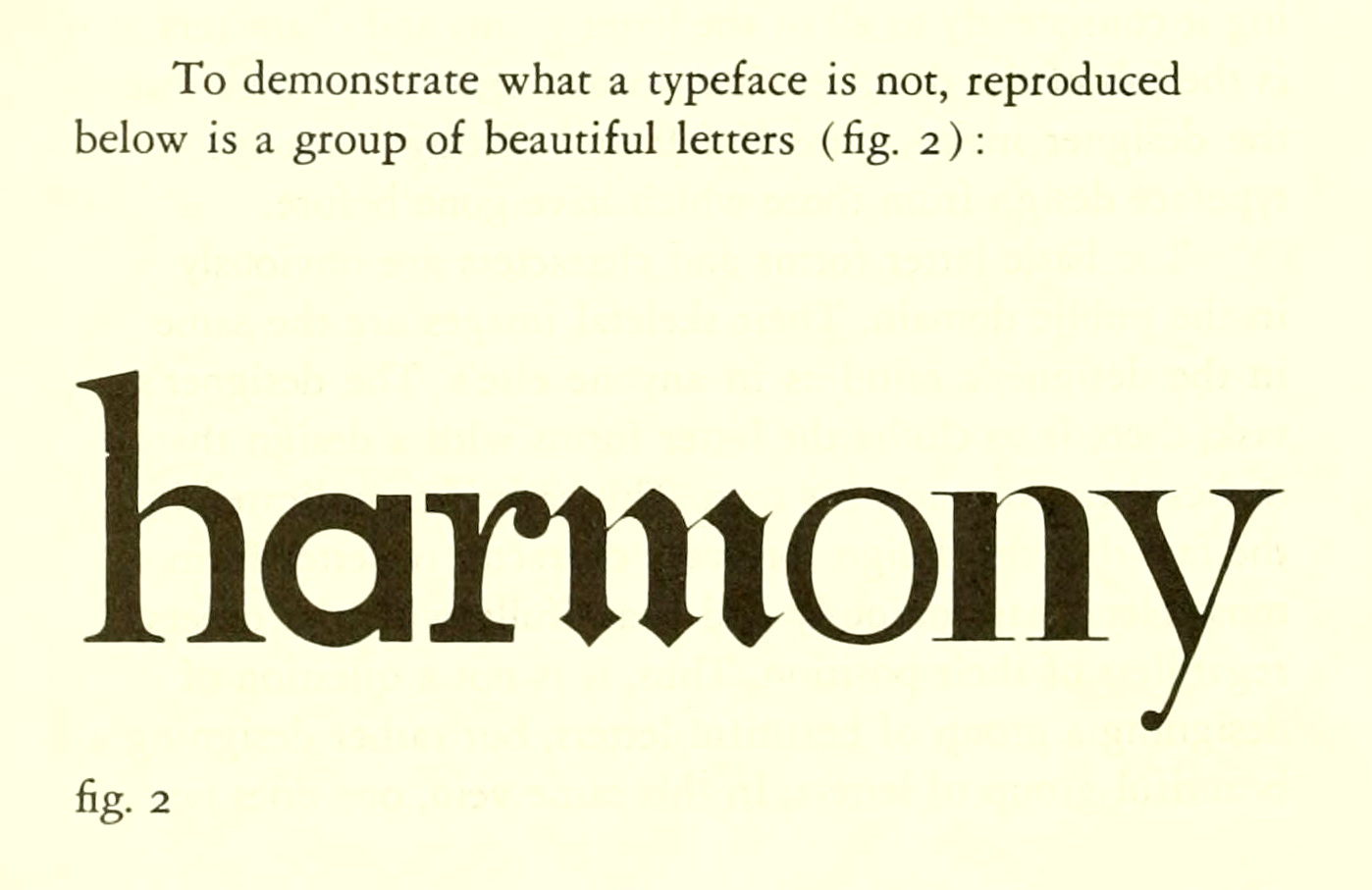

It’s interesting to read Abrams’ and Parker’s responses as they do their best to explain the concept to Wiggins and the other members. One of the company statements submitted to the subcommittee contains a now-famous summation of the craft:

“Thus it is not a question of designing a group of beautiful letters, but rather designing a beautiful group of letters.” — Mergenthaler Linotype

To my knowledge, this is the earliest appearance of a quote often credited to Matthew Carter or Walter Tracy. It’s not clear if either man contributed to this document, but as staff at Mergenthaler, they may have. The author could also be Mike Parker, a witness at the hearing, or Steve Byers, Mergenthaler’s Director of Typography at the time.

Not all type manufacturers presented statements in favor of copyright protection. Castcraft Industries, a Chicago outfit that copied designs in metal, photo, and later digital, was obviously opposed. Among the arguments made by their legal representative was this strong one:

“The Copyright Office would face tremendous difficulty examining originality and creative authorship in typefaces, since the requirements of such examination are beyond the capability of the Copyright Office as presently staffed.” — Howard B. Rockman

Mergenthaler also refuted Dan X. Solo, the prolific replicator of old type who had submitted a 1974 argument against copyright protection.

There are many other interesting tidbits in the supporting evidence submitted by the witnesses. Appended to Mergenthaler’s statement was an article by James Mosley on classification systems, prefaced by this comment:

Concern was expressed at the November 6, 1974 hearing before the Copyright Office whether it is possible to have a classification system so as to permit determination whether a particular typeface design is, in fact, original. Such a classification system can be established — in fact, several already exist!

Both the British and German governments currently have typeface design classification systems. There is also a well known classification system called Vox which basically classifies typeface designs historically. … In short, there exists today various classification systems for typeface designs. If the Copyright Office felt inclined to create its own classification system, Mergenthaler would be pleased to work with the Copyright Office in such an undertaking. — Mergenthaler Linotype

The government never took Mergenthaler up on that offer; otherwise, we’d have yet another national classification system to add to the pile.

I haven’t finished reading the long proceedings from the multiple hearings, but I am sure there are many more nuggets to be found. Please comment with your own discoveries below.

Note

- In the US, it is possible to protect a typeface through a design patent, but that is a much more expensive and cumbersome application process. One can also trademark a typeface name, but that offers no protection for the design itself.⤴

A while ago, I stumbled on these hearings while searching for something completely unrelated. Normally I’d just dump a link in Twitter, but there is so much good stuff in the document to share it would turn into a long string of tweets, which is not really what Twitter does best. So consider this an experiment — a return to Typographica for content that’s better suited to the blog.

Thank you for posting this! I think that the difference in terms of the amount of protection offered by copyright and by design patents is significant. AFAIK, copyright protection in the US and in many other countries lasts for the entire lifetime of the offer, plus an additional 70 years. Imagine what that would entail for a type designer who designed a successful typeface at age 25, and lived to be 100. Design patents are for a much shorter length of time.

The idea of design patents comes from Britain in the 1830s, and they exist today in (at least) many European countries. Germany has had them since 1876. While copyright — I believe — is inherit, one must register a design patent. When I worked at Linotype, we registered many, of not all, of our new typefaces with the respective German design patent authorities. The patent had to be filed within six months of the typeface’s initial publication (which means the first time it was shown or teased anywhere), and it only held for a certain amount of time (including possible renewals). I think that the amount of possible protection time varies across Europe, but IIRC, it was about 25 years (including possible renewals).

I often read that the US is the only country without copyright protection for typefaces, and I wonder if that is true. I mean, what countries actually do grant copyright protection for the appearance of a typeface? As opposed to design patents, which are much shorter term protections. And if other countries do grant design protection for typefaces via a copyright of their visual design, has this been successfully tested in court? My fear is not no court anywhere would actually uphold the visual copyright of a typeface’s design, but I would love to read otherwise!

According to this list on Wikipedia, typeface designs are covered by copyright law in Ireland and the UK, but only for 15 and 25 years respectively.

Yes, patents seem to be the best method for protecting typefaces in the US — which was especially evident in the metal era. In fact, the first US patent ever filed was for a group of typefaces by George Bruce in 1842, and many more typeface patents were filed throughout the nineteenth century.

It seems something was happening in the ’70s. I found a document in the Archivio Storico Olivetti from 1972 about this particular topic. The title read “Meeting of experts on protection of type faces, held in Milano — 24th November 1972”. Some extra info found in that document:

Attendance list: Mr. G. Tomasina and Mr. P. Marola (ASSINFORM), Mr. J. Viard (Honeywell Bull), Mr. C. Falcetti (Honeywell I.S.I.), Mr. A. Bravi (IBM Italia), Mr. G. Lo Gigno (Olivetti), Mr. J. Brügge (Olympia Werke AG), and Mr. H. Baruschke (Ransmayer, Berlin).

(…) The meeting proposed by the Italian Association of the Business Equipment Manufacturers, for the discussion of the draft agreement on the protection of type faces.

(…) A tentative delimitation of the field of application of the convention should take into account the following items:

1) protection directed only to a physical set of type faces (i.e. linotype matrixes for typographical use);

2) spacing of type fonts.

(…) The study for the international protection of the type faces was started by the BIRPI, the former organization of Geneva on intellectual property now called WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), as a consequence of a resolution taken on April 1960 by the General Assembly of the International Typographic Association A.TYP.I.

(…) in 1969 the Executive Committee of the Paris Union suggested to include de discussion of the particular agreement among other more important problems on the agenda of the diplomatic conference, which shall be held on May 1973 in Vienna.

(…) The fifth and the sixth meetings of Committee of Experts on type face protection took place respectively on February 1971 and March 1972. The report of the last meeting will be considered as a basis of the final draft of the agreement to be submitted to the diplomatic conference of Vienna.

II. Interested organizations

The last meeting of the Committee of Experts on type face protection was attended by the following non-governmental organizations:

1) International Literary and Artistic Association (ALAI);

2) International Typographic Association (A.TYP.I);

3) International Chamber of Commerce (ICC);

4) International Federation of Patent Agents (FICPI).

(…) the only industrial association represented at any meeting was A.TYP.I. Representatives of national typographical industries, all associated to A.TYP.I., were included substantial in each governmental delegation of the participating Countries.

(…) The main philosophic reason why A.TYP.I. is proposing the particular arrangement on type faces is apparently the assumption that the type faces combine both the industrial interests of companies and the artistic interests of the authors.

Howard B. Rockman has it right; who can say if a typeface is original “enough”?

Many thanks, Mrs Ramos, for this. I would love to read some more about ATypI’s rationale as regards the limitation, “protection directed only to a physical set of type faces”, and who proposed this. I hope that ATypI representatives or affiliated type historians will shed some light on this.

As I understand it, you can get a design patent for a font in the US (someone should probably interview David Lemon about it since he was involved). They are good for 15 years. I looked into it and the reason I decided not to get one wasn’t that it’s hard to prove originality (though, that too) but because to keep it valid you must challenge absolutely every violation. That struck me as prohibitive given how many small violations I see and choose not to pursue either for financial or PR reasons.