Neebinnaukzhik (Neebin) Southall (she/they/he) is a designer based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and a member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation. The Chippewa, also known as Ojibwe, is one of the tribes belonging to the larger Anishinaabe people. Southall predominantly focuses on work impacting and involving Native communities, including writing on Native artists and designers; photography encompassing portraits, fashion, artwork, and jewelry; and graphic design projects for cultural and arts organizations and individuals. Southall created and maintains a list of Indigenous graphic designers at the Native Graphic Design Project, one of the few such resources currently available.

In November, we caught up on the state of Native visual design, Neebin’s takes on what the design community needs, and her Native Graphic Design Project. After I transcribed the call, Neebin was generous enough to fill in a plethora of links, references, and knowledge throughout. This interview tunnels deep and spreads wide. Make yourself a cup of tea, clear your tabs, and enjoy. — KS.

KSENYA SAMARSKAYA. Since we’re on a platform that’s all about type, could you fill us in on the typographic history of the Ojibwe tribe, and the Anishinaabe people?

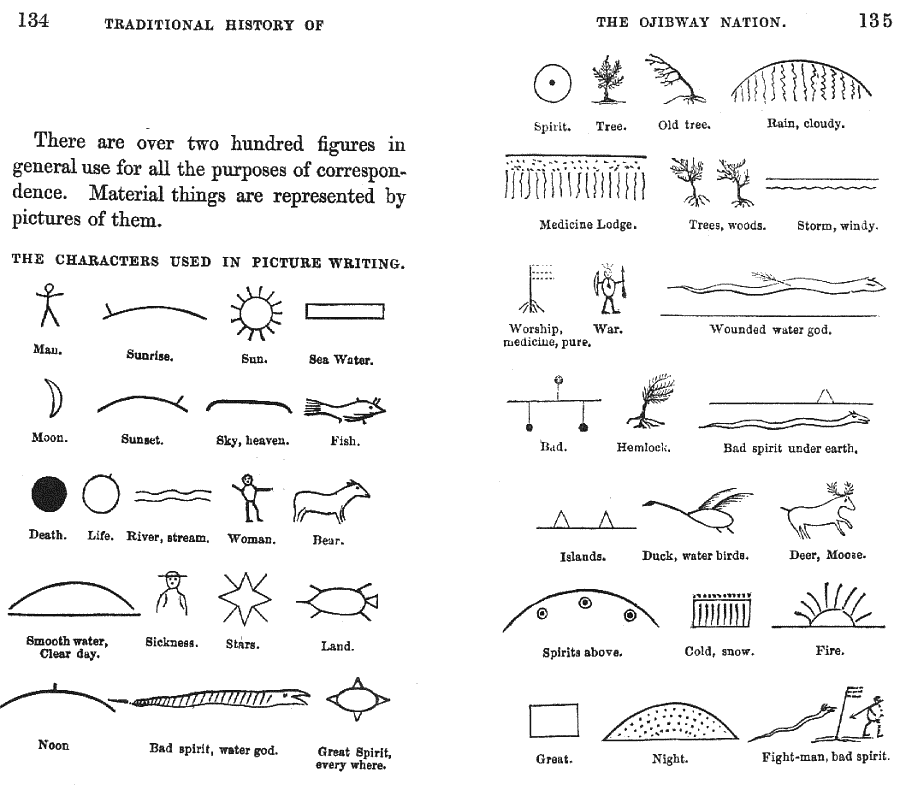

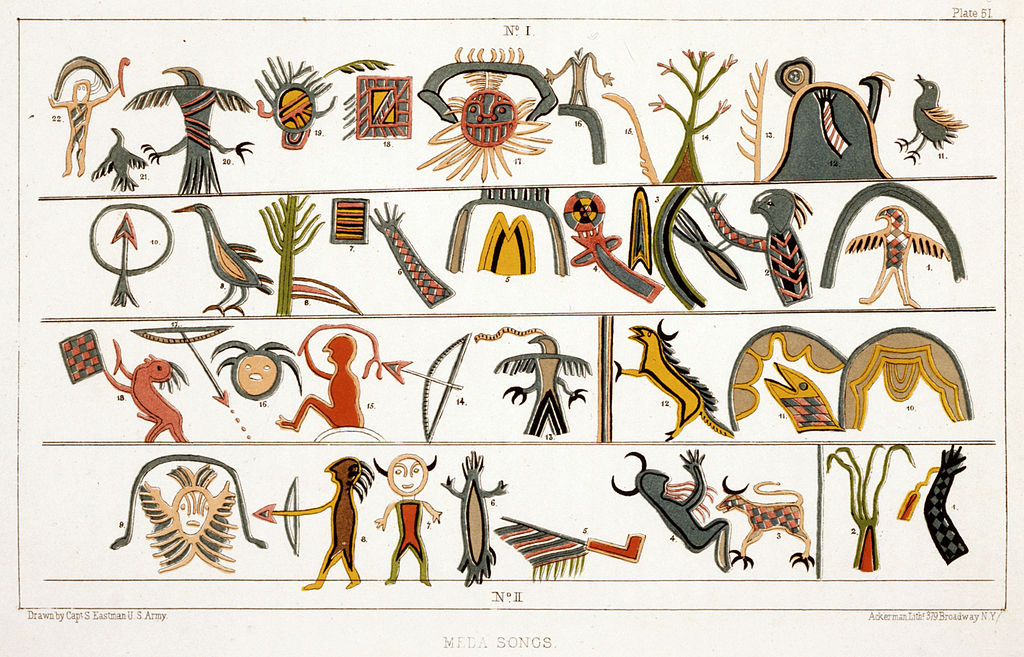

NEEBINNAUKZHIK SOUTHALL. Anishinaabemowin is firstly a spoken language, though Anishinaabe people have also used pictographs to express ideas and stories, such as picture writing on birch bark and petroglyphs. Birch trees are spread throughout the Great Lakes region and beyond, and are a vital part of Anishinaabe material culture. The harvested bark can be easily etched upon for decorative and communicative purposes. Within the Midewewin, a religious society, members have used picture writing on sacred birch bark scrolls. I’m not a member, so I’m not privy to the details, but I do know that these scrolls communicate important and restricted information within the society. Pictographs have also been used to record medicinal plant information on medicine sticks, to denote information for songs, to leave messages on trees and land, and in other contexts such as on weaponry, where they would communicate information about the owner and their exploits. Various Anishinaabe graphic designers and artists today do selectively incorporate pictographs and pictograph-inspired designs in their work, myself included.

After contact with the Anishinaabe, European peoples wrote down Anishinaabemowin using a Latin script with a great variety of spellings, depending on what dialect was involved and who was capturing the information, whether French speakers or English speakers. It’s more recently that spellings have begun to be standardized to the Fiero system. Also, there was a missionary, James Evans, who came through the area and developed the Canadian Aboriginal syllabic system — which is more suited to the sounds of Anishinaabemowin than a Latin script. Cree people, Ojibwe people, and Inuit people use this syllabary. While Cree and Anishinaabe are separate groups, aside from the Oji-Cree, our languages are related as part of the larger branch of Algonquin languages. There are individuals like artist and designer Kaylene Big Knife (Chippewa Cree) incorporating syllabics within her vibrant beadwork-inspired illustrations, and designer and artist Joi T. Arcand (Muskeg Lake Cree Nation) creating laser-cut syllabic accessories through her brand Mad Aunty. Publication designer Sébastien Aubin (Opaskwayak Cree Nation/Metis) recently created the first Cree monospaced font intended for coding.

Anishinaabe designers are also working with typography in digital and print media and product design. Many Anishinaabe bands have tribal newspapers and newsletters. We are writing in Anishinaabemowin in both Latin script and syllabics. Ogoki Learning Inc., headed by Darrick Baxter (Marten Falls First Nation), produces language apps. The National President of the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada, Mark Rutledge (Little Grand Rapids First Nation/Lac Seul First Nation), is in talks with Adobe about a type project in his role as lead designer of Animikii. Other skilled Anishinaabe designers include Dwayne Bird (Cree/Ojibway), Keith Grosbeck (Chippewas of the Thames First Nation), Sarah Agaton Howes (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), Joshua Hunt (Ojibway), Mariah Meawasige (Anishinaabe), Adrian Nadjiwon (Chippewas of Nawash First Nation), Tessa Sayers (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa/Metís/Cree), and David A. Shilling (Chippewas of Rama First Nation), among others.

KS. Do you personally read and write Anishinaabemowin?

NS. I use Anishinaabemowin, but I don’t write it in syllabics. I dabbled in syllabics years ago. I figured out how to write my name, and for a while I had something pieced together for my website’s logo. My mom had different language books and worksheets in the house, which included information on syllabics. I was trying to learn when I was living with my family, but it’s challenging given that I’ve grown up in regions far from where learning syllabics would be more of a norm.

KS. What does being a Native graphic designer mean to you?

NS. Different people navigate it differently, but for me, I think about how we incorporate Indigenous worldviews into the work we’re doing. I strive to positively represent Indigenous peoples, aesthetics, and visual systems in the work I do. I’m always cognizant of my impact on and my responsibilities toward my communities. When you’re part of a tribal people, you’re more aware of yourself as part of a greater whole. I think about how I interact with clients and how my values impact my underlying work philosophy.

If you’re collaborating with tribal people, you have to approach them with respect. Here’s an example: I was working at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian as the PR and web coordinator, and we were doing an exhibition with the Jicarilla Apache Nation. There weren’t many Native people on staff, so the museum shop manager Ken Williams Jr. (Arapaho/Seneca) and I went up to coordinate with tribal members from the Arts and Crafts Department. I was doing the graphic design and promotions for the show, such as the advertising, signage, and invitations, and when we went up there, we spent time with them. A time or two we purchased artwork. I took photos, and they showed us how they made basketry, because it was predominantly a basketry show, though other art forms were included as well. Once, after showing us how materials were harvested, they took us on a picnic. There’s an element of cultural protocol and relating that can happen on the non-design side, those soft skills of how you’re working with a person, right? There are certain things about how you approach somebody in a social setting — a cultural respect that is important to the overall process. Ken knew how to interact with the elders to put them at ease, which was very important to having a successful exhibition.

As a Native designer and arts writer, I frequently work with people from tribal backgrounds that are different from mine. That requires a certain amount of humbleness in the process. You have to be a good listener. You realize that, “Okay, there’s a lot of things that I don’t know,” so it becomes more of a collaborative process. I also take a lot of initiative to research and read books about different cultures and their art. I took the Institute of American Indian Art’s Native American Art History certificate to broaden my understanding. I bring an art history perspective into my work. I look at art and design and see where they feed into each other. I am very interested in Indigenous visual systems and aesthetics. I want to understand what people are communicating visually: the meanings of certain symbols, materials, patterns, colors, and so on and so forth. That way, I’m informed when I’m talking with others. In Native communities, creativity and art are typically highly valued, which, in my opinion, uniquely prepares us to work within design fields.

It’s important to look to the past with an eye for the future. We are preserving, reclaiming, and building culture. Once colonization took hold on this land, it became very difficult to be a Native person due to forced assimilation and genocide and everything that goes along with that. Our cultural ways were and are devalued. It was hard even for our parents and grandparents. At this point in time, we have a lot more personal and group power to be able to stand up and be proud of who we are and where we come from. There’s still societal racism and systemic barriers, but in some ways it’s easier for us today. There’s room for us to flourish as Native people. We have opportunities to heal our communities. There are opportunities to embrace where we come from and bring our cultures into our work. And there’s a lot of Native designers who may not necessarily be going down the cultural route, but are working in the design mainstream. We have people doing excellent work across the design spectrum, and there’s room for us all.

KS. A lot of the stuff you mentioned: listening, cultural sensitivity, understanding human differences — do you think it makes you a better designer when working with non-Natives, or on non-Native projects?

NS. I would think so. I definitely think these considerations flow through your attitude of how you treat other people, whether they are Native or not. I think any designer who is trained properly knows that you have to be willing to listen to a client and be flexible. There’s an extra layer when you’re working with cultural aspects, because you have to make sure that you’re using things properly. I do think that mindfulness translates well to other situations. As a designer, you have skills that somebody else doesn’t, and they’re hiring you for your knowledge. But at times, there can be a bit of arrogance in design circles. It’s good to be confident, but it can be problematic if you have too much of that going on. So I do think that cultural aspects of humbleness and respect can be beneficial to being a practicing designer.

KS. Can you tell us about the Native Graphic Design Project?

NS. It began when I was a student attending Oregon State University’s small yet excellent graphic design program. Many of us came from diverse backgrounds, and my graduating class was a tight and supportive group. Our teachers created many design projects to be open-ended; they gave us the parameters and let us work them out how we wanted, so students would often incorporate personal interests. If someone loved graffiti, they might do a project that incorporated those elements, or if somebody was religious, they might incorporate that.

I was interested in bringing aspects of Native cultures into some of my projects. For our senior projects, we were to dig deep into a particular subject. I was about twenty years old then, with a lot of questions. I realized that I wasn’t learning about any Native graphic designers in my classes, so I wondered, “Where are the Native designers?” There were two other Native students going through the program — I was friends with one of them. There weren’t any Native design anthologies, to my knowledge. There wasn’t much of anything. Social media hadn’t taken off like now, so it was even harder to find similar people. There was a lot less information then. I began to do research. I kept wondering, “What is the state of Native graphic design?” For the first part of my senior project, I put together a research paper involving that question, and for the second part, I dove into learning more about my own Anishinaabe culture and creating work from it.

After some digging, I found the names of different Native graphic designers and kept track of them. Superstar designers Ryan RedCorn (Osage) and Victor Pascual (Diné/Maya) were among the first names I came across. This marked the beginning of the Native Graphic Design Project. I kept finding designers, and the list has grown over the years. I regularly have people contact me with information. Since then, I began professionally writing about Native design and art, so the Native Graphic Design Project has led me to where I am today.

I think the project started off with my personal need to know that there were other Native people out there and I wasn’t alone. Unfortunately, a lot of curriculums and textbooks across the academic spectrum are very Eurocentric. Representation of diverse designers has been limited, though that seems to be shifting. People are having conversations on major design platforms that I really didn’t think was possible back then. When I was young, you would hear decolonization discussed in certain spheres, but definitely not in the design mainstream.

KS. How do you feel about the decolonizing conversations that have been happening in the design community?

NS. I think it’s vital that people are exploring these subjects. We need to interrogate our assumptions and dismantle white supremacy, which are insidiously embedded within many design communities. I am grateful that I have been invited to share my ideas as a Native designer on major platforms, whether in First American Art Magazine or via AIGA. Dori Tunstall, the first Black dean of a faculty of design, has pushed the conversation of respectful design and has been a great advocate for Native peoples. She has personally been supportive of me and elevated my voice along with other Indigenous designers, such as Sadie Red Wing (Lakȟóta/Dakȟóta), a talented colleague and educator who has spoken up about the issues impacting Native designers. As the National President of the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada and formerly the president of the Arctic Chapter, Mark Rutledge (Little Grand Rapids First Nation/Lac Seul First Nation) has used his platform to expand conversations about Indigenous design. In just the past few years, I have seen more in-depth conversations emerge, and I’m glad for that. We definitely need more well-positioned people who are willing to hold space for and uplift diverse perspectives.

There’s also room for improvement in some conversations involving decolonization, whether inside of or outside of the design community. One thing that rubs me the wrong way is when decolonization is discussed in North America and yet Native peoples are sidelined or left out. Decolonization can become a limp buzzword. You can’t discuss decolonization without acknowledging place and Indigenous people. We’re here. I feel like some conversations can get a little too abstract and disconnected. [Eve] Tuck and [K. Wayne] Yang’s Decolonization is Not a Metaphor investigates some of these issues.

KS. What are your thoughts on the state of design education? What could those who are teaching do to help expand the industry?

NS. One of many things I appreciate about my design education is that my teachers, particularly Andrea Marks, Christine Gallagher, and Jen Bracy, were very tapped into the concept of being a responsible designer and transmitted that mindfulness to us. Design isn’t just about aesthetics, it’s also about the role you play in shaping society. You need to understand your impact as a designer, and not in an egocentric way. We have to be responsible for the work we do. We need to be willing to look at how we fit into the larger picture. I think that there should be a critical lens on designers, because there are times when graphic designers have been responsible for creating and perpetuating racist and sexist imagery, been involved in environmentally destructive projects, and otherwise been a part of societal problems. We haven’t always been heroes.

Inviting excellent designers from diverse backgrounds to speak is a great way to expand students’ minds and expose them to different perspectives. When I was a student, Yossi Lemel came through OSU. He’s an Israeli designer who spoke about issues in his country such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He was very brave in his convictions, and used design as a method of criticism, even at risk of personal harm. I had a chance to meet him and ask him questions. I also met Bulgarian-American designer Luba Lukova, who made a strong impression on me with her visual metaphors and hand-drawn aesthetic. Being exposed to designers who use their work to address pressing issues was influential on me as a young Native designer. Access and exposure to respected professionals is important. Things seem to be shifting, but as we all know, there’s been such a focus on a particular set of white male superstars in the design world, to the extent that other people get left out when they should not be. With more content available and accessible online these days, educators have no excuse not to show a range of work.

KS. You mentioned racist imagery and social responsibility. Do we want to touch on any hot-button topics, like the various appropriations of Native patterns or imagery, or the 2020 Land O’Lakes package redesign?

NS. To be honest, I’d rather talk about the innovation and creativity of Native designers instead of bringing more attention to the foolishness of non-Native designers. These subjects take up so much space that could be better devoted to elevating Native people. I want to see talented Native designers and artists given creative opportunities. I want to see us in the driver’s seat. I want to see us mentioned beyond controversies. I want to see more examples of what is done right. Native communities are full of mind-blowing amounts of creativity, and most non-Native people have no idea unless they go out of their way to learn. That needs to change, and that changes by media outlets and educational resources covering Indigenous arts and cultures.

All that said though, I thought I’d mention that the story of Land O’Lakes is a little more complicated. At one point, commercial artist Patrick DesJarlait (Red Lake Ojibwe) was responsible for one of the versions of the woman on the packaging. I’d be interested in knowing what he thought about the project, though he has since passed. Granted, the imagery was stereotypical, and the whole thing was awkward considering that Native people are typically lactose intolerant. A change was due.

KS. What else would you want to make sure non-Native designers are aware of?

NS. Everyone would benefit from learning more about Native art history. The designers we learn about, the different art movements, the European art history — they all inform the assumptions that people have and the work that people create. I’m not advocating for inappropriate instances of appropriation. Rather, I wish that Native art history was fundamentally taught in art and design schools, because I think it would promote an understanding that what comes from here is actually incredibly rich, multifaceted, and valuable. I also think it would cut down on the cringe-worthy “Native-inspired” designs that non-Natives do. It seems so strange to me that here we are in the Americas, and yet so many students don’t know anything about where they are. There are hundreds of distinct tribal cultures here. As much as I’ve devoted my adult life to learning about Native arts and spent time immersed in the Native art world, there’s still so much that I don’t know. Berlo and Phillips’ Native North American Art and Mithlo’s Manifestations: New Native Art Criticism are some good places to start learning. Kramer’s Native Fashion Now is the ultimate eye candy and a great showcase of the innovation happening in the Native fashion world.

I would really love to see print and digital anthologies on the work of Native graphic designers. That’s something I’ve wished for for the past decade. I want to edit and write some myself, and collaborate with others. Over the years, I’ve seen an abundance of amazing work that deserves recognition. I can think of all kinds of subjects that could be covered. There could be a book about Cherokee design, from Sequoyah (circa 1770–1843) and his development of the Cherokee syllabary to how Cherokee is available on Apple products and Google as the result of efforts of Cherokee Nation members Joseph Erb and Roy Boney. Someone could cover the vibrant Indigenous graphic design scene in the Southwest, as exemplified by the work of Indige Design Collab members Eunique Yazzie (Diné), Shon Quannie (Acoma Pueblo, Hopi, Mexican), and Brian Skeet (Diné), or say, the work of award-winning art director and graphic designer Kevin Coochwytewa (Hopi). And of course, I’d love a roundup of Anishinaabe design. There could be books about logos, poster designs, activist designs, and more. Honestly, the possibilities are endless. Let’s get to work.

This interview is published in conjunction with Neebin Southall’s Letterform Archive article on the early-twentieth-century lettering of Angel DeCora.

[…] on a respectful relationship between herself and Samarskaya, who previously interviewed them for a Typographica article and, in one of her first actions as TDC managing director, asked them to co-curate a […]