Neuromarketing: Takeaways for Marketers

“Sleep on it” - some of us hear this expression very often. But did you know that you can take this expression literally?

Sleeping before making an important decision can improve the quality of that decision.

But what does this say about us, that a good night’s sleep helps us be more rational?

In this article I’m going to dig more into this topic:

- Of how we think;

- If we are as rational as we think;

- How we make decisions;

- How we can take all this knowledge into marketing.

But let’s start with this interesting word in the title: “neuromarketing”.

The roots of neuromarketing started back in the ’50s when Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays coined the term “Public Relations”, because “Propaganda” was a hated word during and after the second world war.

He was suggesting that people are irrational and that their decisions can be influenced with the help of crowd psychology and psychoanalysis. I totally recommend the BBC series “The Century of Self” to find out more about this. I’ve seen it twice, but I plan to revisit it.

Fast forward to the 21st century, neuromarketing emerged as a science that wants to map neural activity to consumer behavior to help marketers craft more science-based campaigns. Neuromarketing takes qualitative and quantitative research into the future.

Chapter 1: How rational are we?

Most of us think of ourselves as being conscious and deliberate creatures, but are we?

Back in the ’60s, the first versions of the rational choice theory were formulated. They stated that when we make decisions we make lots of calculations, we take into account the potential decisions of other actors in the process and that we make a cost-benefit analysis. Emotions don’t play a role here, and the social structures we belong to, don’t affect our choices.

Hmmm...but we are social creatures, we belong to tribes that are connected by rules and principles. Can we make decisions outside those principles? Turns out that it’s very hard to do this.

40 years later, Daniel Kahneman wrote his acclaimed book “Thinking, Fast and Slow”. He received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering work with Amos Tversky on decision-making. His research says that there are 2 models of thinking in our brain dubbed as System 1 and System 2.

- Inside System 1, thinking and deciding are fast, on autopilot, intuitive, slow-learning, and emotional.

- Inside System 2, thinking and deciding are slow, deliberate, they take effort, they play by the rules, and minimize emotions.

These two systems lay in our brains. System 1 is older than the other from the evolutionary perspective. There’s a great metaphor out there where System 1 is compared to an elephant, while System 2 is the rider (developed by the NYU psychologist Jonathan Haidt).

The rider symbolizes the rational brain. He’s responsible for direction and planning, but sometimes he can get trapped into overthinking. On the other hand, the elephant relies heavily on its freeze, fight and flight instincts. It’s emotional and prefers short-term outcomes over long-term ones. He likes to get things done fast. For example, the rider is the one telling you that you need to exercise, eat healthily, focus on saving money. The elephant just loves instant gratification and might opt for that extra ice cream before sleep.

Now, let me give you an example of how the rider and the elephant function and how this can affect our society.

There was an experiment performed back in 2009 that looked at more than 1,000 rulings made in 2009 by eight judges. Here are the conclusions:

- The likelihood of a favorable ruling peaked at the beginning of the day;

- There’s a decline of favorable ruling over time from a probability of about 65% to nearly zero;

- Favorable ruling spikes back to about 65% after a break for a meal or snack.

There’s a fascinating podcast episode about this and similar situations, on Hidden Brain, with Daniel Kahneman. The episode is described like this:

“Psychologist Daniel Kahneman says there are invisible factors that distort our judgment. He calls these factors ‘noise’. The consequences can be found in everything from marriage proposals to medical diagnoses and prison sentences. “

It’s a gem, I’m telling ya!

Now, this experiment with the judges is both fascinating and scary. We are talking about the same persons deciding differently before and after lunch? It seems that the rider just fell from his elephant...

Chapter 2: How buying decisions are shaped

Now, let’s revisit Daniel Kahneman a bit. Together with Amos Tverski, he introduced the notion of “cognitive bias” to define people’s flawed responses to decision-making.

Let’s take a quick look at some of them:

- Confirmation bias - the tendency to look for information that confirms our own preconceptions. For example, let’s say Robert does not believe in climate change. He would always read articles and research that stand by his belief. He wouldn’t read the information that contradicts his ideas;

- Endowment effect - the tendency that people often demand more to give up on an object than they would be willing to pay to get it;

- Fundamental attribution error - the tendency to overemphasize personal factors and underestimate situational conditions when explaining other people's behavior. Here’s an example: Maria is driving, while she is suddenly cut off by James. Maria says that this is happening because she knows James is a jerk and an unskilled driver. She does not think that there might be another explanation...maybe his wife is in labor at the hospital.

- Gambler's fallacy - the tendency to think that future probabilities are changed by past events when in reality they are unchanged (e.g., no one won at the roulette in the past hour, so winning is close);

- Halo effect - the tendency for a person's positive or negative traits to extend from one area of their personality to another in others' perceptions of them. When this bias occurs it can prevent someone from accepting a brand or a person, based on a belief in what is good or bad. For example, in my opinion, Nestle is bad, because its business leaders think that water should be privatized, and this contradicts my beliefs.

- Hindsight bias, also known as “the knew-it-all-along phenomenon” - a memory distortion phenomenon where people perceive past events as having been more predictable than they actually were. You knew all along who the killer was in your favorite movie, right?

- Hot-hand fallacy - the expectation of streaks in sequences of hits and misses whose probabilities are, in fact, independent (e.g., coin tosses, basketball shots);

- Illusory correlation - the tendency to identify a correlation between a certain type of action and effect when no such correlation exists.

- In-group bias - the tendency for people to give preferential treatment to others they perceive to be members of their group;

- Mere exposure effect - the tendency by which people develop a preference for things merely because they are familiar with them.

Now that we know all this, it’s time to take our decision-making discussion even further and enter the marketing realm.

People have many beliefs and behaviors, some controllable, others not, that interact and influence our consumer actions and choices. Through various techniques, it is possible to identify factors that tend to influence most consumers in predictable ways.

And here comes Robert Cialdini who back in 1984 wrote a book called “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion”. He explains the psychology of why people say "yes", and how to take this know-how into practice. His book is based on thirty-five years of rigorous research.

He developed 6 universal principles that can be applied not only in marketing but any aspect of life. These principles can guide us into becoming better persuaders, but also how to defend ourselves against persuaders. Let’s look at them from a marketing perspective, and how you can apply them in your strategies:

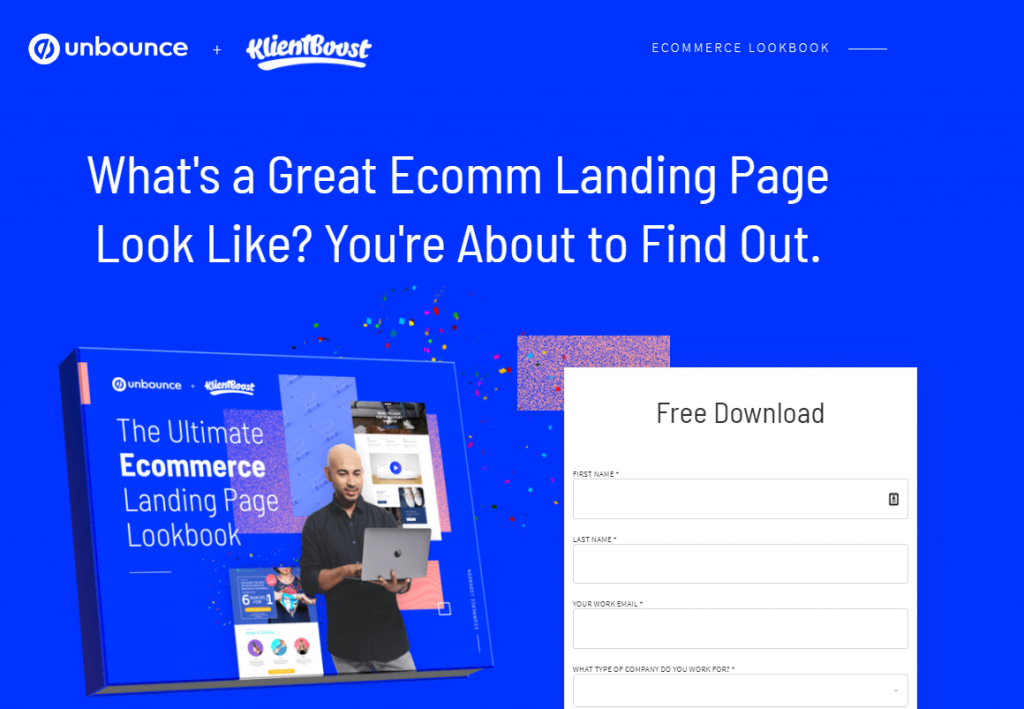

- Reciprocity

People are wired to treat people like they treated them. It seems we hate to be indebted to others. For example, if you have an awesome ebook on your site, visitors would feel ok to leave their email address to get that piece of valuable information. Just don’t push it and ask for too much from them.

- Consistency

Once we take a stand, we will face lots of pressure to behave consistently with that commitment. This is what explains why unpredictable people are less likely to be liked and to thrive among others. Going a bit further into marketing, when a brand commits to something it should stay by its commitment. Also, when a website has a certain design and messaging, it is advisable that ads, emails, social media messaging, are consistent with that design and copy.

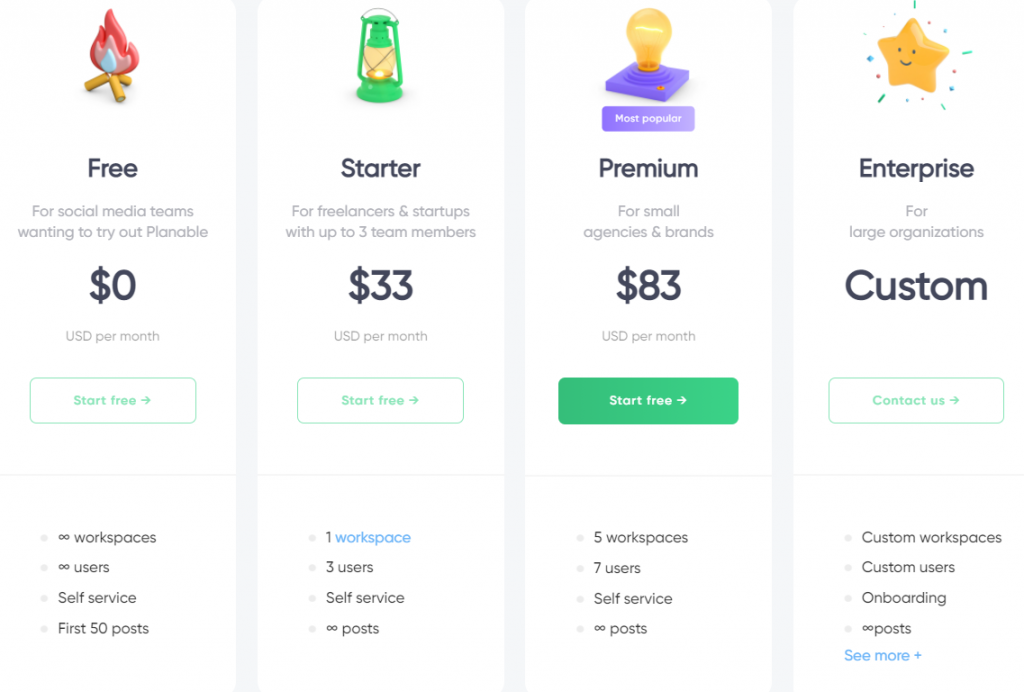

- Social proof

We will often copy the behavior of others, and we need to have our actions validated by others.

Here’s an example of social proof used on the pricing page by the folks at Planable. They use a “most popular” badge for one of their plans.

Here’s a marvelous example from Nat Geo’s show “Brain Games''. In this experiment, people are shown a card with 3 straight lines, named A, B, and C. They have different heights. Next, on a separate card, they see a single line. They have to decide if that line has the same height as A, B, or C. When someone makes a choice, he has to move behind the card with the name of the choice. The first 9 persons choose A. But they’re a decoy, and the answer is wrong. The rest of the people (with very few exceptions) feel the pressure, and do not go with their gut, but with the “wisdom of the crowd”.

What does this say about our rational behavior?

Now, how can you apply this principle in marketing? Well, you can use reviews, case studies, testimonials to back up your story.

- Authority

We have a tendency to obey authoritative figures.

In Jun 2021, Cristiano Ronaldo (one of the world’s greatest football players and a health fanatic) removed two Coca-Cola bottles during a press conference at the Euros, and asked for water. What happened next? Coca-Cola’s shares’ price fell, meaning a $4bn loss in value.

This explains why influencer marketing is so powerful these days, especially with the rise of social media.

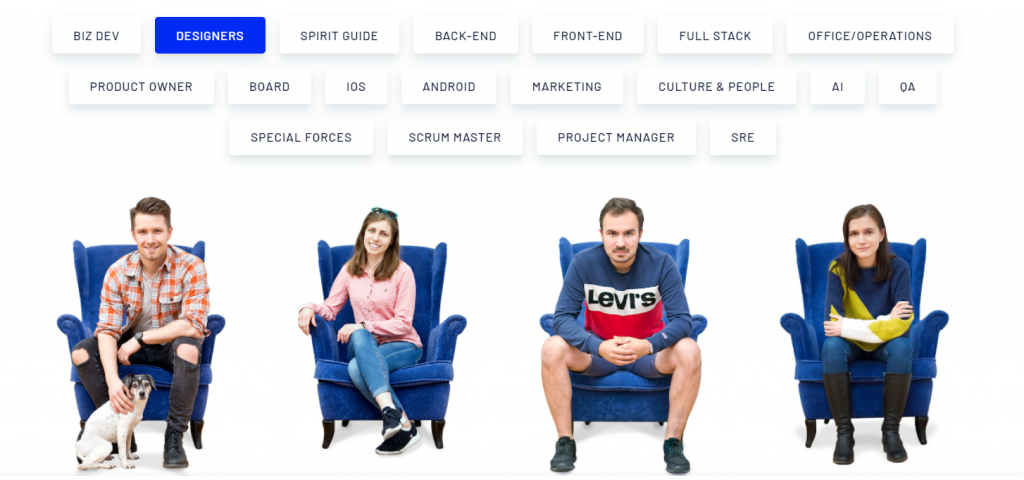

- Liking

The more we like someone, the more we can be persuaded by that person. For example, we often judge people based on how they look. If a person is likable, we trust her more.

This is why you can make the most of your “About us” website page, and try to put some friendly faces there. Here’s an example from Tooploox, a software development company.

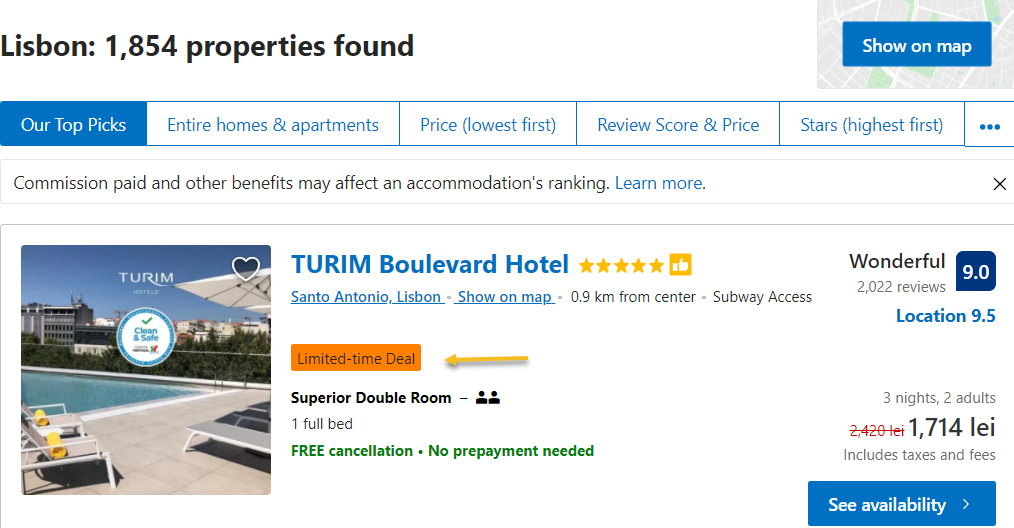

- Scarcity

When you believe there's a short supply of something, you want it more. This induces a FOMO feeling, meaning the “fear of missing out”.

The folks at Booking are doing this, with their available properties.

Chapter 3: Is there a "buy button" in our brain?

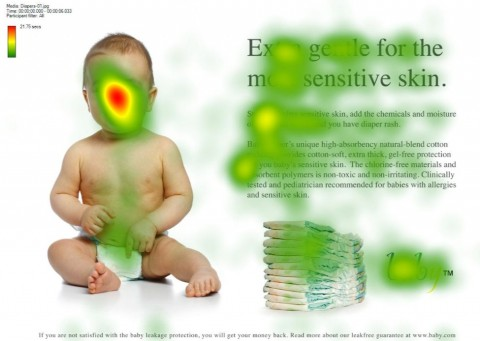

Neuromarketing uses functional MRI (fMRI) to analyze how our brains work under certain stimuli. This is why people argue that neuromarketing is trying to find the “buy button” inside our brains. But the truth is that neuromarketing provides us with valuable insights regarding human emotion and decision-making processes.

Here’s an example: neuroscientists at UCLA scanned the brains of people watching Super Bowl commercials. They concluded that a Doritos ad stimulated empathy and connection, while other commercials provoked fear or anxiety.

It seems that the neuromarketing techniques are more reliable than traditional techniques such as surveys or user interviews. Why so? Because people aren’t able enough to describe and predict their own cognitive processes, while, on the other hand, brain responses offer more objective insights into their behavior. But there are some limitations as well. People argue that these experiments are made in a safe environment (a lab), and in the real world, behavior can change.

But, fear not, no “buy button” got discovered and neuromarketing needs a technology that is not easily available.

Still, there are some ethical concerns around this. What if companies with big budgets, will misuse neuromarketing conclusions?

Let me give you an example. Children are sensitive to ads because their neural inhibitory mechanisms are not yet mature. This means that they can easily be manipulated. Advertisers can take advantage of their lack of self-control. This is happening in traditional marketing as well: McDonald’s and Disney partnered to serve toys with Happy Meals.

So, some ethical concerns arise here, when dealing with vulnerable categories: children, old people, people with diabetes, etc., and regulations are needed.

Chapter 4: Applied neuromarketing

Neuromarketing strategies can help you:

- Understand why a customer chooses your product or your competitor’s product;

- Encourage users to perform actions that have value for you (eg: clicking on a call to action button, buying something, writing a review, etc.);

- Create higher engagement with your prospects;

Here are some practical ideas:

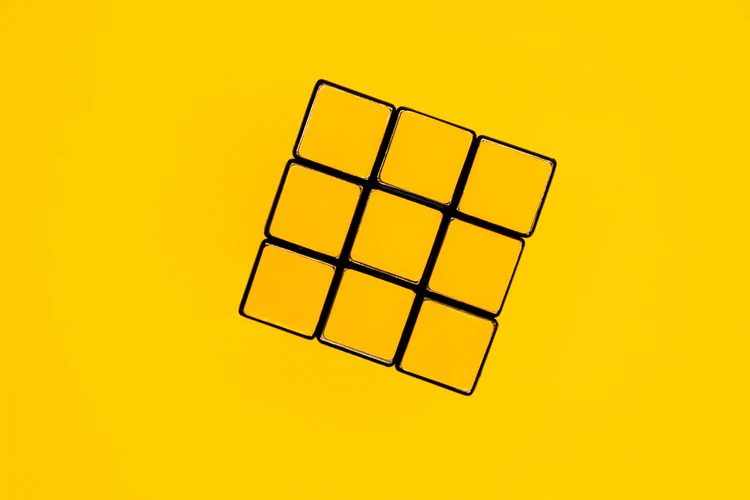

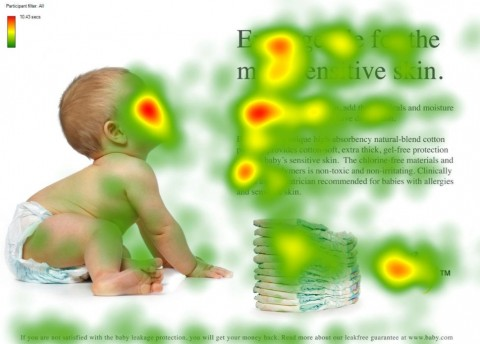

- Use people faces in ads, but pay attention to the focus of the gaze

Most of us are attracted to babyfaces. This has been known for years, and advertising has included babies in their ads for a while now.

Yet, what changed?

An eye-tracking experiment showed that if the baby looks straight to you, your focus would be on the baby.

But if the baby looks at a product, or some copy, your focus shifts.

- Using sound and color to sell a product

Powerful bass makes people subconsciously attend to dark objects, or white color attracts more when compared to black. This explains why in web design whitespace gets a lot of attention. Also, products with light colors sell better when placed on the top shelf, while products with darker colors perform better on the bottom shelf

- Creating an efficient product design process

I have an interesting example for you here. A 2016 study concluded that people with a high body mass index (BMI) prefer a thinly shaped bottle, even if the drink is higher in price. Now, why does this happen? It seems that in the Western culture thinness is associated with economic value.

This can go in two directions: both healthy and unhealthy drinks manufacturers could profit from this.

- Unpleasant weather conditions can lead to hedonic consumption

It seems that when people are feeling down because of the weather, they try to compensate for their mood by an increase in hedonic consumption. This has a stronger effect on women because they are somewhat more susceptible to weather-related influences on mood.

- Anchoring

The first piece of information a potential customer receives is very important. It sets the tone for their purchasing behavior. Neuroscientists have discovered that we are rarely able to evaluate the value of something based on its intrinsic worth, but instead, compare it with the surrounding options. For example, when a product is valued at $100, but then there’s a 40% discount, and you see the second price of $60, the $100 price serves as an anchor.

- Impulse buying and its stimuli

Research suggests that 62% of in-store purchases are made impulsively. This can give some hints to advertisers on how to communicate, present promotions, and make use of all sorts of sensory stimuli to sell.

Chapter 5: How to build your own experiment

No, I’m not talking about a neuromarketing experiment, using fMRIs :)

I’m talking about an A/B testing one, where you can take an existing conclusion in neuromarketing and see if it works for you and your website visitors.

Let’s assume you want to use a hero image on your homepage using people’s faces. How can you make the change, measure its impact, and decide whether it was a successful one or not?

You run an A/B test.

For this you will need to use:

- A control version of a page;

- A variation of the same page based on a single change - your hero image in this particular case.

Next, it’s time to plan your A/B test:

- Define your business goals, your key performance indicators, then your metrics that will sustain your KPIs and goals. Eg: you might want more clicks on the main CTA that lays inside the hero image.

- Make sure you can collect the data that you need to calculate and understand the goals selected above. Google Analytics can help you out here.

- Formulate a hypothesis. It can be something like: “we expect a click-through rate growth of X% if we add people’s faces to the hero image. That X% can be established taking into consideration historical data. Now, you can test this on mobile devices only, specific geo, the fewer variables the more conclusive the test.

- Prepare the experiment. Tools like Google Optimize or Omniconvert can help you prepare for the test. These tools can show you when the test has reached statistical significance, meaning there’s a clear difference between the control and experiment. It can tell you how long the experiment should run, based on your sample size. Now, for small sample sizes, you might need weeks till you see the results. The tools allow you to split the traffic equally between your control version of the page and the experiment one.

So, what are you going to test out first?

Wrap up

Neuromarketing wants to provide us with some valuable insight regarding decision-making processes. What it CAN’T provide: tools to control our mind.

It’s true that neuromarketing needs regulations, but so does traditional marketing.

Conversion rate optimization makes strong use of neuromarketing and consumer behavior principles. But, use them wisely and respect your customer. Don’t forget about Cialdini and his “reciprocity” principle -> people are wired to treat people like they treated them.

Featured image by EKATERINA BOLOVTSOVA on Pexels