V&A Dundee’s Night Fever explores the design history of the world’s most famous clubs

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture looks at the design of clubs like London’s Ministry of Sound, Berlin’s Berghain and New York’s Studio 54.

“Night clubs have the power to mean a lot to people on a number of different levels,” Night Fever: Designing Club Culture curator Kirsty Hassard says. She points to Manchester’s Haçienda, whose black and yellow Peter Saville-designed stripe pattern has even infiltrated non-clubbing culture. When the club shut down, its contents were auctioned off – from its disco ball to pieces of the floor. “People paid a lot of money to own a tangible piece of that club,” Hassard says. “It shows the elevation of design through meaning and memory.”

V&A Dundee’s new exhibition explores the design of clubs from the 1960s to the current day, with an international outlook. While New York is home to many of the clubs featured, there are locations from further abroad like Space Electronic in Florence, Italy and The Mothership in Detroit, US. Scotland too gets a mention with The Rhumba Club and Glasgow’s Sub Club.

Throughout, it looks at the interiors, furniture, graphics, sound and technology designed to bring the club nights to life. The exhibition’s content has been filtered by the scene’s often temporary nature, explains Hassard. “A lot of nightclub spaces were very ephemeral spaces,” she says. “You would have an interior for a certain period of time and then it was stripped out.”

While that may have limited some of the objects to display, it also leads to unexpected finds such as cheese slicers and mouse traps that have been fashioned into themed invitations. “Obviously the owners of them thought they were so special and that’s why they survived,” Hassard says. “They’re witty and tongue-in-cheek pieces of design.”

Though some of the designed objects might be limited, there’s plenty of graphic work on display. “These tended to be the objects that people keep,” Hassard says, of the show’s collection of club tickets and posters. There’s over a decade’s worth of Scottish club posters designed by Edwin Pickstone. Saville’s graphics for Manchester’s Haçienda night club have also been reimagined on a gallery wall.

One reason why clubbing may have brought out designers’ inventive sides is that spaces often survived on shoestring budgets, according to Hassard. That’s particularly true of the scenes in post-war Italy where studios like Gruppo 9999 and Superstudio – usually fresh university graduates – would design spaces with limited resources. “These spaces wouldn’t survive in the long run, and that’s one of things that was really attractive to the designers,” Hassard says. At the other end of the spectrum were themed clubs like Area in 1980s New York, where huge budgets allowed designers to strip out interiors every eight weeks and fulfil a new creative vision each time.

Some objects have survived from the nightclubs, and they help to tell a story about the interiors of the time. “You get a sense of the total designed look of these places which is what they were going for – everywhere having a particular look,” Hassard says. She singles out a Vitra chair which was preserved from a 1960s nightclub in Bolsano, Italy. A photograph of the space shows 60s-era interiors like a pastel pink colourway and abundance of Perspex furniture. Furniture design was crucial for clubs, Hassard explains, for setting the scene and creating the look. “You look at that one object and imagine how exciting an interior that would have been,” she says.

The ephemeral nature of these spaces, which were often home to radical politics and underground movements, relates to another of the exhibition’s themes: unrealised clubs. These include drawings for a nightclub designed by Muppets creator Jim Henson and the isometric models for the Ministry of Sound II. Both of these never came to be but the renders show exactly what they were intended to look like, explains Hassard.

The exhibition also looks at fashion design. A series of photographs documenting New York’s Studio 54 highlights the glamour provided by fashion designers like Halston and Steven Burrows. “A lot of nightclubs the idea is to be seen by people and project a certain identity,” Hassard adds. In 1990s Belgium, Walter Van Beirendonck (part of the Antwerp Six) was also designing clothes especially for the clubbing scene.

As clubbing has evolved over the faces, so too has its reputation. The exhibition’s final section looks at developments in the German techno scene with the establishment of Berlin’s Berghain and Tresor. It also explores technology design, from synthesisers to the lights that illuminate the dark spaces. “There’s more of a feeling of ‘we’re doing something incredible here and we should be protecting the architectural models’,” Hassard adds.

An exhibition designed with “disco moments”

The exhibition has been designed by Munich-based studio Oha. Co-founders Sami Ayadi and Jan Heinzelmann set out to create a space that reflected the themes of the exhibition, with an emphasis on lighting and graphics inspired by the real-life venues. A neon Night Fever sign opens the exhibition, while a colour-changing light display creates shadows of queuing visitors on the wall.

Lights are set up on rigs throughout the exhibition, and details aim to be period accurate. “The idea is to use the right lights from the right era,” the designers say. This extends to other details of the exhibition. In an early section, a black and white grid wallpaper is taken from a pattern at Italy’s Superstudio, for example. In a later room, Peter Saville’s Haçienda stripe has been reinterpreted on a wall.

Ayadi and Heinzelmann have used the practical elements to create a sense of mood too. For example, sections are divided by a metallic silver curtain so that areas are distinct but still evocative. “It doesn’t just divide the section but it gives the 80s section a disco look with references to Studio 54,” the designers explain.

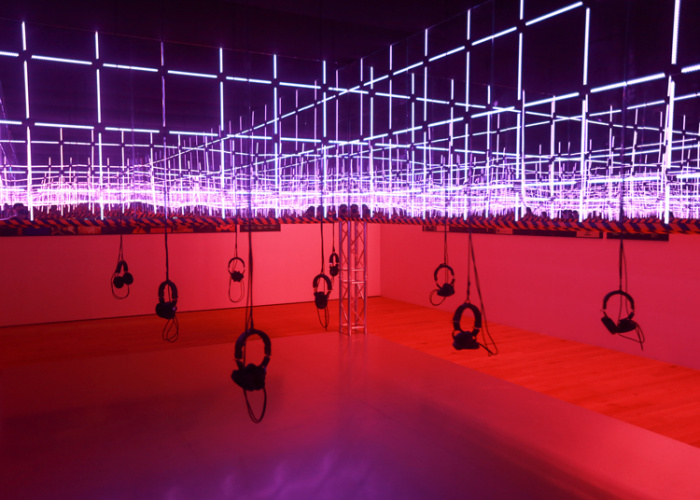

One of the highlights of the exhibitions is an “infinity room” which doubles as a silent disco, Ayadi and Heinzelmann say. Visitors enter a mirrored pathway which have LED strips. “The mirrors give you an infinity feel,” the team adds. There are headphones for visitors with different playlists, from house to disco. “You really get the feeling like you’re in a nightclub – it’s a disco moment where people really start to dance,” they say.

Creating an “authentic view” of clubbing

Glasgow-based design studio Too Gallus has created Night Fever’s identity, which showcases four eras from clubbing history. The studio has also designed a series of idents for the exhibition’s social channels and to play on displays at the venue. “The identity could have easily slipped into a parody of itself,” studio founder Barrington Reeves says. “First and foremost, we wanted to speak to people in that world and been involved in clubbing.”

Reeves describes clubbing as “second nature” to him; his father was involved in the Haçienda and his mother was involved with the Northern Soul movement. The research phase involved talking to relatives and family friends to get an “authentic view of what clubbing was like at the time”, he says. This helped the studio to resist a cliché view of the clubbing, according to Reeves.

The identity spans four periods of clubbing, with references to Jewel’s Catch One bar in Los Angeles and 1980s nightclubs in Miami. These visuals include familiar icons like smiley face pin badges as well as the more technically-advanced scene of contemporary Ibiza nightclubs. For observant viewers, there are ‘easter eggs’ – hidden clues – in each of the scenes, Reeves explains. For the 1980s club era, the lighting fixtures are accurate to the time, for example.

“We felt like the identity would be successful if one person who experienced clubbing at the time saw it and recognised it,” he says. “The right people will see the right things.”

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture is running at V&A Dundee from 1 May 2021 – 9 January 2022. Tickets start from £6 and more information about booking and opening times is available on the V&A Dundee website.

The exhibition also looks at fashion design… with shoeless, jewelless and wigless mannequins. Terrible!