Search this site

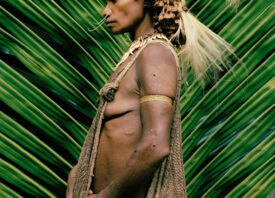

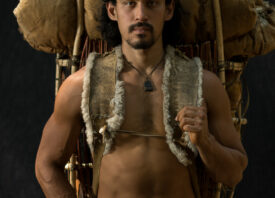

The Last Hunter-Gatherers of Borneo

In 1894, British colonial official Chares Hose described the Penans, a nomadic hunter-gatherer people living in the headwaters of the rivers flowing through the ancient forests of the Kingdom of Sarawak — now known as Borneo. Hose described something the people of Europe hadn’t known for several millennia: a way of life predating the advent of agriculture.

“They are great hunters, being able to move through the jungle without making the slightest noise, and have a name for the slightest living thing, which name is known even by the small boys,” Hose wrote, his admiration betraying a propensity to underestimate the people of a culture far older than he dared dream. “They are wonderfully expert in the use of the blowpipe, shooting their poisoned arrows with such precision that is must be said they seldom miss even the smallest subject aimed at.”

Hose’s awe would have been better reserved for the ability of the Penans to collectively resist the concentrated effort of the government to destroy their way of life, most recently when loggers set forth in the 1980s to invade their territory in the name of profit.

Determined to protect their age-old way of life, the Penans developed non-violent civil disobedience in conjunction with a Swiss born environmentalist named Bruno Manser, who was searching for a way of life without money. In the year 2000, Manser disappeared without a trace, and the remaining nomadic groups finally settled on the land in an effort to protect their last forests from loggers.

In 2014, Swiss photographer Tomas Wüthrich began visiting the Prnanas, spending six months at a time with a group lead by Headman Peng Megut, who still practice foraging today. Despite the fact that they live in land that has been logged and degraded, they still have maintained a largely intact rainforest, with the police going so far as to protect them from the Lee Ling timber company in 2018.

In the new book, Doomed Paradise (Scheidegger and Spiess), Wüthrich beings together the work he has made over the past decade documenting the last of the Penan nomads along with a selection of their myths organized by linguist Ian B.G. Mackenzie, which are published here for the first time.

The book has been designed with the Penan in mind: it is printed on moisture-resistant paper made from limestone so that it will be durable in the Borneo rainforest. What’s more to create Rockpaper no tree was felled and no drinking water consumed — offering a vital lesson in the use of technology to us all.

Doomed Paradise is a stunning portrait of the people and their disappearing way of life that takes great measures to bring together a small community with a world it would never otherwise meet. There is an honesty and a truth that pervades the world, evident in an early photograph of a pair of well worn feet standing proudly on the jungle floor that later appear with the caption, “’We don’t want roads or cars,’ says Peng. ‘Our feet are our cars, and they take us up mountains and across rivers.’”

As we accompany Wüthrich in his travels with the Penan, a powerful truth makes itself clear. The ancient way of life, in which people lived off the earth for thousands of years, created balance and harmony between wo/man and the environment. It is more honest, authentic, and exact — fueled by need rather than illusion or want.

This way of life, in which ecology operated as intended, may be disappearing but it’s hard to ignore the thought that after climate change does it’s worst, we’ll be back here once more, albeit perhaps without the wisdom and guidance of those who know how to survive without the comforts of modern life.

All image: © Tomas Wüthrich